How a character says hello: writing “barks” for video games

There is a certain type of dialogs in video game writing, called barks.

Barks are the lines and onomatopoeias delivered mostly by NPC (Non Playable Characters) or by the player’s character, in given situations (triggers).

For example, while passing a city’s gate, the player will hear a guard shouting: “We don’t like people like you around here…” or “Welcome, stranger!” A bark can also be this enemy provoking you during a fight: “Is that all you got?”, “I was expecting better…” and other variations. A dialog between two NPC you hear arguing is also a series of barks. In any case, the player won’t be able to react directly, unlike interactive dialog.

A bark is one of those elements that makes the player feel like the fictional world truly exists, and is evolving on its own.

When I started writing for video games, barks didn’t strike me as the supreme test nor as an essentially fascinating aspect of game writing. I was used to writing for other media, mainly for screen and theater, and I thought writing barks was just about finding 36 variations of the same line (even if barks can also be unique pieces of dialogs, and in that case it is closer to typical dialog writing). But progressively, this openly simple exercice proved to be more complex and interesting than I expected. I’ll try to share some of my thoughts on the subject here.

What do we use “barks” for?

A bark has many functions, and the first one is to inform the player. It is a systemic dialog.

If the player is hurt, one of his companions will tell him he has to heal himself. If the player enters a forbidden zone, a guard will tell him to go away. Or if the player passes by a merchant who wants his attention, the shopkeeper will remind him he has some interesting things to sell.

For a fight bark, the writer will often write two, three, ten variations of a given situation/trigger. If the situation is: the player is running out of life, it will be x variations of barks from the enemy reacting to the player being hurt. Examples: “This is the end for you…”, “Just give up already!”, “I told you it wouldn’t end well…”, and so on.

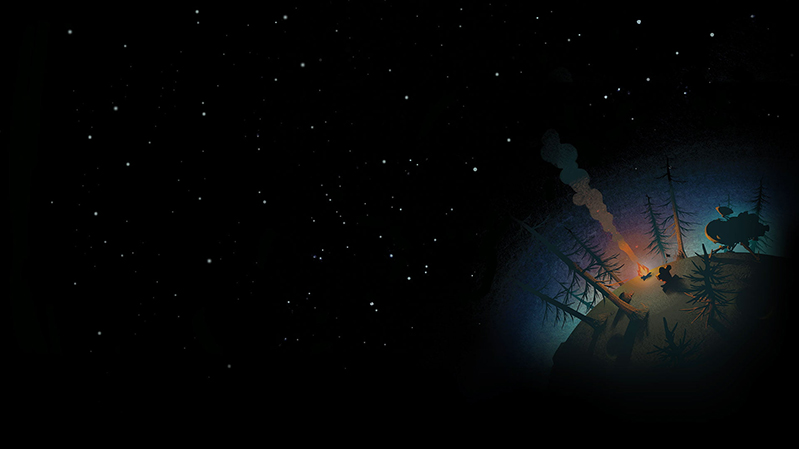

For this fight bark in A plague tale (see illustration), the situation/trigger is: the enemy is badly hurt. The writer came up with this bark of the enemy saying: “Ah… I’m just a bit… rusty…”, basically telling the player that he’s winning the fight, but in a more subtle way. Of course, the player sometimes has information on the enemy’s health in the HUD (the interface) but, as we know, in video games like in any other field, an information could be best repeated…

From one video game to another, in similar situations/triggers, barks are often really much alike. And these same barks can be quickly annoying for the player, when they are repeated too regularly or when triggers aren’t well designed (read this article on the “most annoying barks”)… And a well known example would be this line: “Never should have come here“, repeated by many enemies in The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (Bethesda Softworks, 2011).

The (endless?) possibilities of barks

One of the main functions of barks being to inform the player, it’s easy to stop here when writing. If the situation/trigger is the enemy is hurt, let’s just put “I’m hurt…” and go write some more substantial dialogs. But barks can be more than that. So, what can the writer do with them?

Spread information about the lore

In video games, lore defines the storyworld, and more precisely the fictional environment in which the player evolves. The lore is less or more complex, less or more detailed, and the way lore elements are spread in the game environment depends on many factors (I may write about that one day).

Barks, since they are triggered in given conditions directly related to the world, can become a way to enrich this lore. For example, this character who salutes you will do it by referring to specific gods from this world. Or, if he belongs to a faction who despises yours, he won’t salute you but will urge you to go away, or insult you. A simple “Go away” will let the player understand that this type of characters hates this other type of characters, especially if the bark repeats regularly.

Barks can also use specific language elements from the video game universe, like Orwell’s newspeak does in 1984. Even if the player doesn’t know the universe well and may not understand these terms right away, it will reinforce his immersion by contributing to the richness of the lore.

God of War (Santa Monica, 2018) Example of fight bark : “Gonna drag your carcass to Asgard”

Characterizing

In video games, NPC are often characterized initially by the group they belong to (faction, social level, job, species, etc). Therefore the barks will be identical for every NPC coming from the same group. But here again, the writer can go further and use barks to characterize the character way beyond its group.

When we write what we can call “Greetings barks” for characters that we want to characterize, typical questions of characterization must be asked: how is a shy character going to say hello to the player? How a character who admires the player will say hello to her? What about if he hates her? A character whose main characteristic is to be “spacey” will maybe just tell the player that he’s not willing to talk (“Hmm?”), or just ask “What?” with a distant tone. There is dozens of ways to say hello, and depending on the character or the situation, one will fit while the other won’t.

(suspicious) “Hmm… what do you want?”

(absent-minded) “Yes?”

(welcoming) “Glad to meet you!”

(annoyed) “What’s that again?”

(overjoyed) “I thought you would never come!”

(shy) “What can I do for you?”

(uncomfortable) “What are you doing here?”

and so on…

Of course, most of these examples require specific intentions from the voice actors so… voice recordings. If you only have text, then you have to keep this constraint in mind.

A simple “greeting bark” can tell a lot about a character, even before the dialog starts: it will give clues on his mood, his relationship to the player or to the world…

By extension, a bark can possibly introduce a situation. If a NPC welcomes you with a happy “Hello!” before telling you, in the upcoming dialog, that his harvests burned on the morning and that he needs your help, this warm “Hello!” was definitely a badly written bark… Maybe a “I was expecting you!” or “Finally, you’re here!” will fit better, and also encourage the player to start a dialog, because he feels that something is going on.

Tell more with less words

In another article, I talked about the narrative potential, which is anything in the story world that isn’t told, but evoked. On this subject, I strongly recommend Marie-Laure Ryan‘s work.

Let’s take the example of a series of barks in Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura (Troika Games, 2001), which is one of the first RPG I ever played and finished, and still deeply enjoy. In the video below (original video here), the player kills an enemy. Then the dead man’s spirit goes out of his body, and asks the player to resurrect him. If the player clicks on the corpse, the ghost will react and beg. In the video, the player clicks several times on the spirit, revealing a series of barks: “So. This is Death“, “I see… death“,”Aaaaagh! The pain! Please, release me!“” “What is going on?“, etc etc.

As a writer, what could we have done with these variations of barks? We could have written, for example, something like: “I can hear him now…” . Or “She’ll never forgive me!” And maybe the player would have asked herself the question: who/what is this spirit talking about?

By writing these barks with narrative potential, the goal is not only to inform the player about the situation/trigger and the possibilities that arise from it (here: the enemy is dead but can be resurrected), but also to evoke other stories around this character: a past, a future. The player will fill the blanks with her imagination, but you have to give her something upon which to work! This is also a way of managing the gaps in your story and world.

Gaps are a huge subject of world building (I’ll try to write about it someday). There will always be gaps in your story and world. But as I often say, there can’t be gaps where there is no ground!

Transforming a simple bark into a potential dramatic question is a way to exploit the depths of the fictional world, and make the player think that it truly exists on its own.

Create and exploit a gimmick

Unlike a line of dialog that the player will only hear once or twice during the game, a bark will sometimes be heard dozens, hundreds of times. Therefore, a bark has the power to enter the player’s mind and to stay there for a long time… Just like a summer song reminds you of your holidays, or the opening of a TV show reminds you of your childhood, a bark can become a Proust’s madeleine for the player. As an example, all the players of Age of Empires still remember the incomprehensible remarks of the villagers.

A bark can really leave a mark on a game (in a positive or negative way) and its writing become all the more important.

Beyond video game

Barks writing is specific to video games. Yet it’s one of the missions that regularly makes me think about the craft of writing in general.

Why? Mostly because a bark has to be clear and short. The writer has to work with this specific constraint of dialog writing in mind: telling one or several information in only a few words. It leads to the subjects of subtext, characterization… In short: What does this character want to say when he says hello?

Barks writing helps me work on dialogs differently. When I write for movies or theater, I try to use less words when required, or I try to write spontaneously different variations of the same line. But above all, barks writing support my opinion that each medium should always be compared to others in terms of writing and narration, in order to feed into each other.