FAQ – Writers and narrative designers in video games

I regularly receive some questions about careers in narrative design or game writing, to which I unfortunately cannot always answer. I have decided to gather the most frequently asked ones so that those who are considering becoming narrative designers, writers, or narrative directors in the video game industry can find some answers here. I will add sections regularly.

Important note: every career path is unique! I am just one example among many, therefore I encourage you to explore other profiles who may provide slightly different views.

What is the difference between a game writer and a narrative designer?

Some studios may hire the same person for the positions of writer and narrative designer, while larger studios often distinguish the two roles.

It is important to know that both the term “narrative designer” and the recognition of the specialization itself are relatively recent, therefore the definitions can vary significantly from one studio to another… and even among narrative designers themselves. I would also add that in some studios, narrative design missions are sometimes assigned to a game designer or a quest/mission designer.

I will attempt to summarize the main responsibilities of both game writing and narrative design roles, as I have personally encountered them.

Game writer / Writer

The missions of a video game writer are primarily to build the story, create characters, write dialogues and textual elements (from the content of a letter to tutorials and weapon descriptions), write cinematics, the game world’s bible and other lore elements, etc. Depending on the type of game, the narrative means will significantly vary, and so will the tasks of the game writer. For example, for a platform game without dialogues, they may be responsible for designing the levels structure from a narrative perspective, without necessarily writing scripted scenes.

Narrative designer

The tasks of the narrative designer are highly transversal. It involves choosing, building and integrating the tools that will express the narrative through the game. As we are talking about video games, the primary means of narrative expression are the game mechanics and systems. But depending on the project, it may also include the story structure, dialogue systems, environment and other visual elements, audio elements, etc. The narrative designer works closely with all the other departments. That is why it is important, if not necessary, to understand how a game is produced to perform this role.

In both cases, it is crucial to learn how to write and design for interactive projects, because all games are different and require constant adaptation.

Journey

How to break into the video game industry?

Once again, every career path is unique. There are no magical advices, but here are some pointers.

Learning the craft

Apart from the numerous video game schools, there are online resources (including the amazing GDC conferences) to learn about narrative in video games, as well as some reference books listed in the dedicated section below.

Attending video games events

There are many events worldwide that allow you to meet professionals, test games in development, attend conferences, and gradually build a network. Notable events include the Game Developers Conference (GDC) in San Francisco, or Gamescom in Köln (Germany).

Joining an association

Joining an association or participating in associative events allows you to meet people and stay informed about the indie video games scene. You can find associations online based on your geographical location, your artistic or personal interests.

Joining a game jam

To meet people who are starting out or already evolving in the industry, and to join a team and create a small game in a few days, game jams can be a good lead. One of the most well-known game jam is the Global Game Jam.

Building a portfolio

I will detail this question in the following section.

Work, luck, network

As I often like to repeat, these three elements do not work separately. If you happen to come across a producer who you admire during an event, and are able to pitch your next project to them or give them a link to your portfolio, it is because you have worked beforehand and created your own luck by attending that event. The producer may not call you back, but they may remember you when you cross paths again. Or even better, they may recommend your profile to someone else. An effective network is an organic one, and a network is built over time by meeting and working with other people.

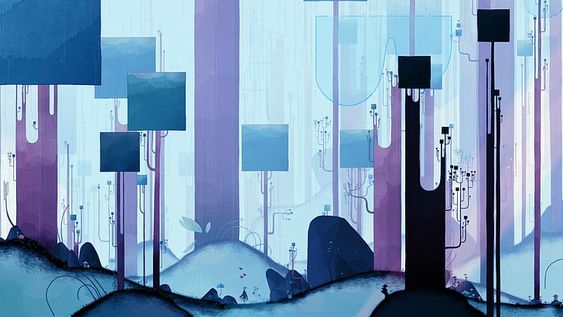

Gris

How to build a portfolio?

Most students from video game schools complete their studies with a year-end project. If you like your project and think it reflects what you can do, don’t hesitate to add it to your portfolio!

If you don’t come from a video game school, you can create a small game yourself using accessible softwares like Twine, Ink or Game Maker. A small and well-crafted game can sometimes be enough to convince a recruiter to call you back. And an itch.io link can easily be added to a portfolio… even the creators of The Stanley Parable made their small Twine game!

For a writer position

Send writing samples of scenes, cinematics or in-game dialogues like barks, etc. Characters bios, world bibles, and other textual contents are also relevant. This will allow the studio to get a sense of your style, your preferred genres… Of course, if you have video excerpts of gameplay sequences you have worked on, even better!

For a narrative designer position

Depending on the job description from the studio you apply to, the elements detailed above for the writer position may be relevant, particularly the world bibles. Also, add video excerpts of gameplay sequences, from which you can provide more detailed information about your previous missions, objectives, and how you approached narrative design for these sequences… If you don’t have any video excerpts, you can still detail your tasks and design approach from your previous games.

Little Nightmares

Books references on interactive storytelling?

On interactive narrative and world building, here is my top 5:

- On Interactive Storytelling, Chris Crawford

- Dramatic Storytelling & Narrative Design, Ross Berger

- Game Writing, edited by Chris Bateman

- Building Imaginary Worlds, J.P. Wolf

- Professional Techniques for Video Game Writing, Wendy Despain

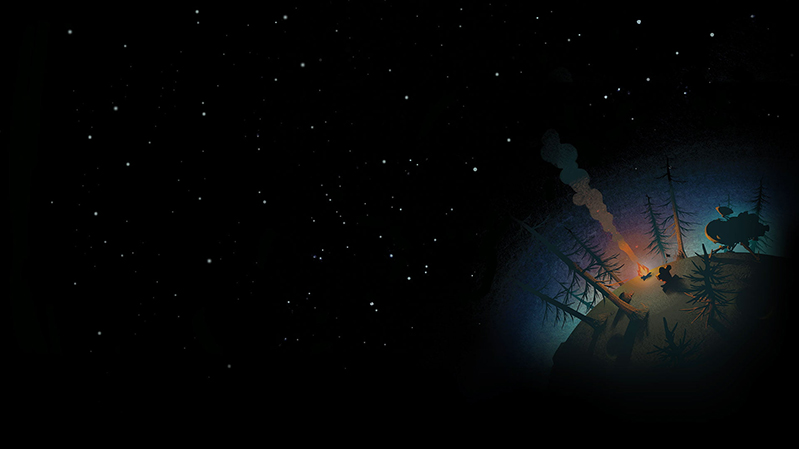

Firewatch

What is the difference between writing for movies and writing for video games?

People keep asking me this, and it is a difficult question to answer in a few lines. To summarize: you don’t write for one medium the same way you write for another, because each medium has its own tools.

Let’s take a simple example: a book is not written like a movie because it does not use the same tools. In the case of a movie: image and sound. From these given tools come possibilities and constraints (writing a screenplay means taking in account editing, scenes must describe visuals and sounds only, dialogues are written for actors to play with specific intentions, etc.).

Video games also have their own specific tools, and interactivity is the most important one. The player is active in the narrative. Learning to write for video games means taking the player into account in the storytelling process.

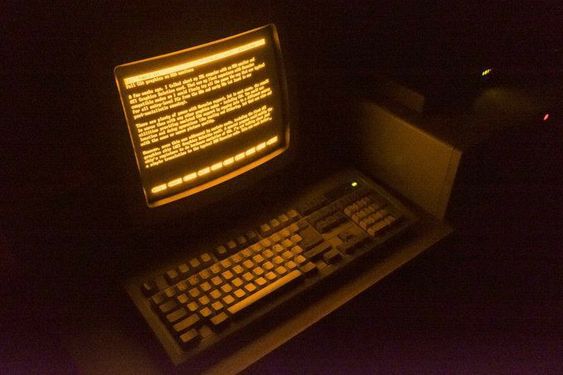

The Stanley Parable